In 2018, DREAMSEA digitized all 124 manuscripts of the collection of La Ode Zaenu in Bau-bau, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. One manuscript among them that catches the eye is entitled Doa Menggunakan Senjata (Prayers on the Use of Weapons), which can be accessed under number DS 0010 00003 in the DREAMSEA database. The manuscript is only two pages long and belongs to the category prayers and divination. The text is written in Malay in Jawi script which is Arabic script adapted to the requirements of the Malay language. Many manuscripts from Nusantara contain mantras. These mantras are generally used to ensure that unwanted and dangerous things will not happen in certain situations under specific conditions. Mantras can also be used to be granted something one desires. After Islam entered Nusantara, mantras changed and from then on also started to include Quranic verses or parts thereof that were uttered in certain situations.

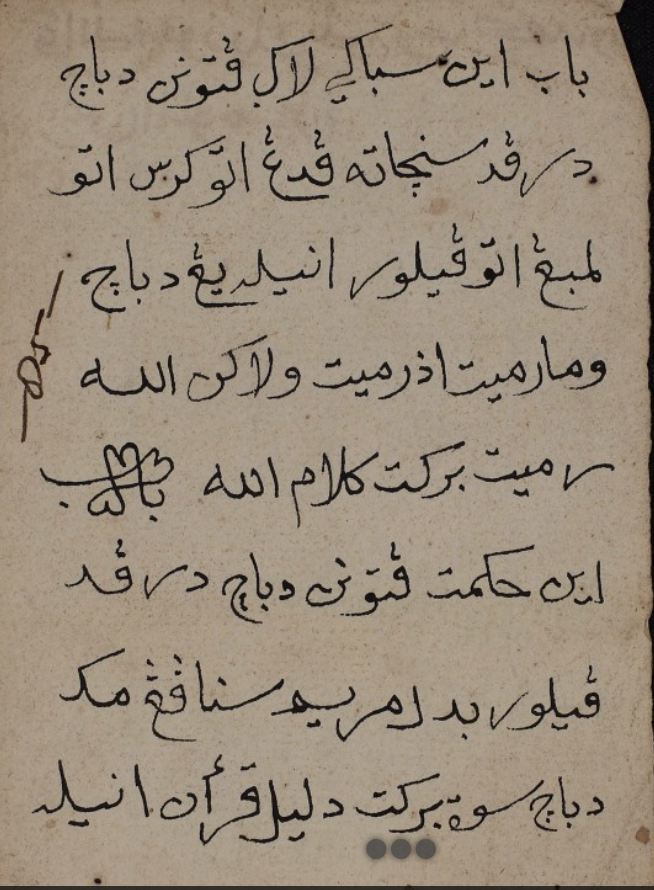

Bab ini sabagai lagu patunan dibaca

Daripada senjatah pedang atau keris atau

Lembing atau pelor inilah yang dibaca

“wa mā ramayta iẓ ramayta wa lā kinna Allāha

ramā<ytu>.” berkat kalam Allah

This Chapter is a song that should be read /

for weapons like swords or daggers or /

spears or bullets:

“wa mā ramayta iẓ ramayta wa lā kinna Allāha/

ramā<ytu>.” thanks to Allah’s words.

Ini hikmat patunan dibaca daripada/

pelor bedil meriam senapang maka/

dibaca suatu berkat dalil Qur’an inilah//

This is the supernatural power that is to be read for

bullets for guns, cannon and rifles. It is

to be uttered for its benefit because it has its source in the Quran

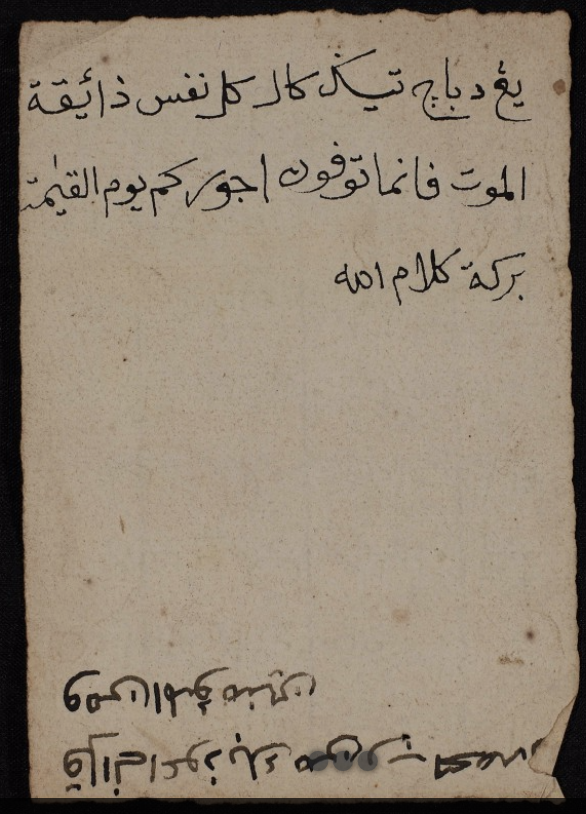

Yang dibaca tiga kali “kullu nafsin ẓāiqatu/

al-mawt fa innamā tuwaffawna ujūrakum yawma al-qiyāmati”/

berkat kalam Allah //

Read three times: “Every soul will taste death, and you will only be given your [full] compensation on the Day of Resurrection.”

because of Allah’s words

The up-side-down text below says:

Qul innī a’ūẓu bika min rabbi yaḥduru

Wa min al-mu’minīn…

Say, “I seek refuge in You from all that surrounds me.”

The text thus mentions various weapons and ammunition: swords, daggers, spears, bullets, firearms, cannon and rifles. It uses two Quranic verses in the prayers to be said before these weapons are to be used. On page 1 recto, the text quotes Surat al-Anfāl: 17 and on page 1 verso Surah Āli Imrān: 185. Both texts essentially say the same: it is Allah who wishes the death of a person and each living being will one day taste death. Interestingly, the first Quranic verse is also included in a manuscript that was digitized by the Endangered Archive Programme (EAP) of The British Library EAP211/1/1/41.

Collection of Bambang Irianto, Cirebon, West Java.

This manuscript carries the title Manuskrip Petarekan (Sufi Teachings) and is part of the manuscript collection of Bambang Irianto from Cirebon in West Java. The Javanese text contains an elaboration on the dhikr of the Shattariyah Sufi Order which aims to guide a person’s heart. Apart from the Quranic verse, it also contains texts on medicine and prayers for specific purposes such as to be able to become pregnant and bear children. The ambalang (Jav. throwing and shooting) mantra is written diagonally downwards in the margin. The text is as follows:

Punika jampé ambalang/

wa mā ramayta iẓ ramayta wa lā kinna/

Allāha ramā//

punika jampé lumpuh salāmun qawlan min rabbi al-rahīm/

This is the mantra to (be uttered before) throwing and firing weapons

wa mā ramayta iẓ ramayta wa lā kinna/

Allāha ramā//

It was not you who threw (a handful of small stones) but it was Allah.

This is the mantra to render weapons harmless salāmun qawlan min rabbi al-rahīm/ (Peace, a saying from the Most Merciful Lord).

The inclusion of Quranic verses in these manuscripts shows that to understand the past, no clear distinction can be made between Nusantara society’s belief in mysticism and the way it puts Islamic teachings into practice (Yahya 2016, 30). Both texts were written by members of the Shattariyah Sufi Order that developed in Buton. One of the leading figures of the order was Syaikh Muḥammad ‘Aydrūs Qā’im al-Dīn ibn Badr al-Dīn al-Buṭūnī who ruled the Sultanate of Buton from 1824 to 1851 and who included the concept of the Martabat Tujuh (The Seven Dignities) in the system he used to govern his realm. The same had been done by one of his predecessors, Sultan La Elangi, who ruled from 1597 to 1633 (Niampe 2011, 46). The concept of the Seven Dignities is part of the waḥdatul wujūd (Unity of Being with Allah) based on al-Burhanpūrī’s al-Tuḥfah al-Mursalah ilá Rūḥ al-Nabī. The Shattariyah Sufi order also expanded swiftly in other places in Nusantara, such as Cirebon in the eighteenth century and also here, the Martabat Tujuh teaching was adhered to. This becomes clear from, among others, a statement made by Mahrus el-Mawa (2016, 156), who said that the Martabat Tujuh teaching influenced 41 Suluk Cirebonan such as the Suluk Bali, Suluk Wragul, Tuhu Lingling, and Bayan Mujahadah. A suluk is a kind of Javanese literary work that contains Sufism or spirituality. In general, the genre is found among people living on the north coast of Java (Machsum 2019, 123). The Sultanates of Buton and Cirebon therefore resembled each other in the way they practiced their Sufi teachings.

In early 20th century, Skeat (1900, 522) wrote in his work Malay Magic that in the Malay world, charms were always used in war and armed conflicts. He divided Malay charms into two types, namely offensive and defensive. If we look at the sentence used in the two manuscripts above, it is clear that it is an offensive charm. Therefore, texts with prayers and mantras related to weapons are linked to the political and social context in Buton and Cirebon at the time. Although located in different geographical locations, both regions had their share of intensive armed conflicts, especially during colonial times. For instance, the Sultanate of Cirebon was engaged in armed conflicts with the Dutch starting in the eighteenth century under the rule of Sepuh V Sjafiudin (1773–1786) and these conflicts continued until the early nineteenth century. Also, the Sultanate of Buton has a long history of war and was engaged, for instance, in the Makassar War that started on 21 December 1666 and lasted until 2 June 1669 (Andaya 1981, 74).

The prayers that were to be said before weapons were used show that, in the past, spiritual elements were used in war and other armed conflicts. The digital availability of the two manuscripts described here may open further possibilities to study the extent of the relationship between mantras, charms, and armed conflicts in Nusantara in the past. In a wider sense, further study of manuscripts may reveal that Sufi Orders and practices played significant parts in the struggle against colonialism in Nusantara.

Further readings:

- Andaya, Leonard Y. 1981. The Heritage of Arung Palakka: A History of South Sulawesi (Celebes) in the Seventeenth Century. The Hague: Nijhoff.

- Yahya, Farouk. 2015. Magic and Divination in Malay Illustrated Manuscripts. Leiden: Brill.

- El-Mawa, Mahrus. 2016. “Suluk Iwak Telu Sirah Sanunggal dalam Naskah Syattariyah wa Muhammadiyah di Cirebon”. Manuskripta (6)1, pp. 145–166.

- La Niampe. 2011. “Unsur Tasawuf dalam Naskah Undang-Undang Buton”. Literasi 1(1), pp. 43–58.

- Machsum, Toha. 2019. “Sastra Suluk Jawa Pesisiran: Membaca Lokalitas dalam Keindonesiaan”. Mabasan 3(2), pp. 125–135.

- Skeat, William Walter. 1900. Malay Magic: An Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula. London: MacMillan and Co. Ltd.

Data Converter of DREAMSEA

Leave a Reply